Review: Rabbit Hill by Robert Lawson - In Which I Am Happy This Is Not The Book I'm Ranty About

[Still reading children's books. Why we have them around is covered in this review. Short version: children's reading program, public schools.]

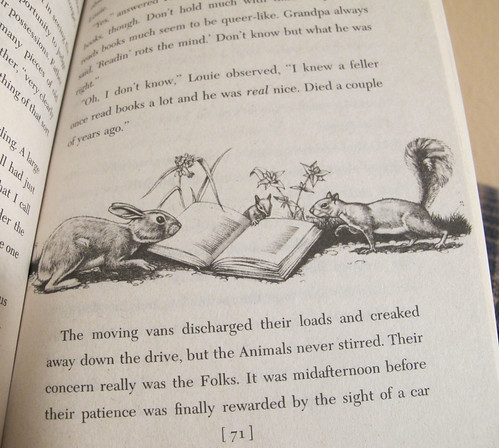

You may immediately recognize - if not the name Robert Lawson - then the style of illustration (images below). The really popular book of Lawson's (when kid-me was reading at the school library anyway) was Ben and Me: An Astonishing Life of Benjamin Franklin By His Good Mouse Amos (which does not have its own wikipedia page, instead you only have this one for the 1953 Disney film). I'm betting that it was suggested reading for American History book reports. I don't remember reading it - though I do remember looking at the illustrations. Rabbit Hill (1944) was somewhat popular at our library, but then it was also a Newbery Award winner, and those usually were put on display during certain times of year.

My memory of the book has to do with my Fear Of Animals Getting Hurt In Books - which is really thanks to other books, not Lawson's.

[Here I will assure you that no animals in the story die, though you're made well aware from the beginning that other little animals have died in the past because various older animals tell stories about it. BTW I'm not going to retell any of the animal stories I read that freaked me out as a kid because odds are high they'll also disturb you to some degree. But I will be spoiling the entire plot of this book, FYI.]

The children's books with animals in them that I grew up reading in the 1970s were a weird mix - I read enough of the older books and the more modern ones, and oddly it's the more modern ones that were often the problem. Animal stories were usually teaching an Important Moral Lesson or going for comedy. But then you had others that masqueraded as a caring story and instead were all about Tragic Thing Happens to Animals. I loathed those. I didn't give a rip if the human lived - I much preferred that the animal not die. (Authors do have that power, after all.) Tragedy where the author kills off the beloved character rather than use alternate means (you know, the old suffering and making it through) - well I always feel that's a cheap shot. Those stories did nothing but upset me, and as an adult they still annoy the hell out of me. I'm specifically not stating the names of them (neither are well known). Let's just say they're worse than Old Yeller for having no reasoning or message in the animal deaths. But then I never did accept "author kills pet/the parents/etc. to give child a growing up exercise" as a Message.

(Tangent! I feel similarly about stories that go out of their way to have an unhappy ending for all the human characters because Suffering Is Literature and happy endings are not. If the author mixes both tragedy and happiness in, fine. That's closer to the reality I know. But an ending where everyone goes away miserable, alone, never to be loved, suffering nobly, release only in death, etc. - um, why do I want to read that? If tragedy was the default human condition - and if people could never see beyond that - why would we need that reminder in books? But that's me. Oddly I can take the "everyone dies" in horror, no problem. It's when it gets all "everyone dies, because, literature" that I quibble.)

Happily this is not the story Lawson wrote in Rabbit Hill. Kid-me was very relieved about this, because there were hints it might be.

From the beginning we learn that people are a threat (guns, traps, poison, etc.), as are dogs. But people don't have to be that way - there are people that are deemed the right sort, who can be lived with - it just takes a while to figure out if they are the right sort. The rabbits and other animals learn to work around those threats, and more importantly band together with their neighbors to plan for the safety of their community. (Foxes get along with herbivores, so you know we're in a fantasy here.) All of the animals have personalities and quirks that you can't help comparing to humans. Father Rabbit is a southern gentleman who will talk endlessly (great vocabulary, btw), and Mother Rabbit worries about everything that might possibly happen.

Lawson has put together a detailed backstory on the specifics of how rabbits plan in order to stay safe. Here Little Georgie (rabbit) has a talk with his father about a journey he's about to take. It's the short version of rabbit education, p 36:

"Now, son," he said firmly, "your mother is in a very nervous state and you are not to add to her worries by taking unnecessary risks or by carelessness. No dawdling and no foolishness. Keep close to the road but well off it. Watch your bridges and your crossings. What do you do when you come to a bridge?"

"I hide well," answered Georgie, "and wait a good long time. I look all around for Dogs. I look up the road for cars and down the road for cars. When everything's clear I run across - fast. I hide again and look around to be sure I've not been seen. Then I go on. The same thing for crossings."

"Good," said Father. "Now recite your Dogs."

Little Georgie closed his eyes and dutifully recited, "Fat-Man-at-the-Crossroads: two Mongrels; Good Hill Road: Dalmatian; house on Long Hill: Collie, noisy, no wind; Norfield Church corner: Police Dog, stupid, no nose; On the High Ridge, red farmhouse: Bulldog and Setter, both fat, don't bother; farmhouse with the big barns: Old Hound, very dangerous..." and so on. He recited every dog on the route clear up to Danbury way. He did it without a mistake and swelled with pride at Father's approving nod.

So there's a lot to worry about - but the way to deal with it? Thinking things out, planning, and helping your neighbors when you can. That's A Lesson, but it's not hitting the reader with the Unsubtle Mallet that's often used in kid's stories. (That mallet comes in later.)

The plot centers around the house that this entire little community of animals live around. The people who've just moved out didn't garden or do much with the property and as a result the entire neighborhood of animals have lived through lean times when its come to food. What's interesting is to notice that, when new people move in, the neighbor humans have also lived through the same sort of problem, and the new business helps them as well.

The suspense: will the New Folks be good neighbors to the animals? Spoiler, yes.

Father tests them by running in front of their car - they break and let him pass, and then put up a sign the next day:

And because I wanted to show more illustrations:

You know the New Folks are nice because they have lots of books. The locals aren't quite so nice - they think having too many books is a bad thing ("Grandpa always said reading rots the mind"), but then they also try to solve all their animal problems with traps, poison, and guns.

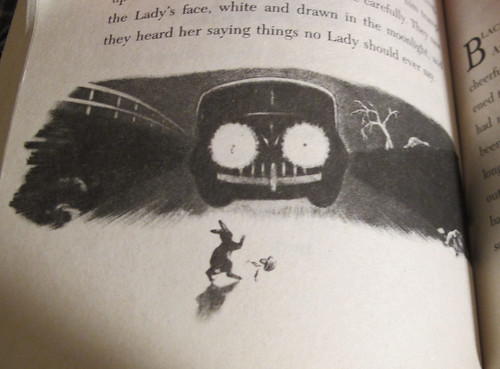

Here's the part where kid-me worried that we were about to go into Tragic Thing Happens to Animals territory. Georgie has to make an evening food run to another farm. And on the way home...

As an adult I'm still kind of amazed at this drawing - or at least how much it stuck in my memory. It's very small, but the fuzziness of those headlights, and the tiny basket in the process of falling - it says a lot with a limited composition.

Ah but Little Georgie isn't dead - the New Folks find him in the road and carry him into the house. Then everyone in the animal community worries because they have no idea what's happened to him.

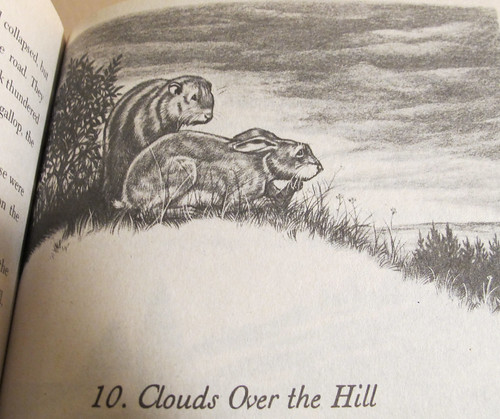

This image I'm sharing just as an example of how expressive Lawson's drawings can be. I dare you to not want to hug that poor woodchuck. Not to mention Father rabbit.

It might make you feel much less sad when you know the woodchuck's name is Porkey.

They finally get news that Georgie's alive because a mouse reports seeing him through a window, and seeing the people taking care of him - but no one knows for sure if he's ok. And then Uncle Analdas, who's played the crotchety old man/rabbit part, goes all batshit conspiracy theorist. It's at this point you might ask yourself if this kind of thing would fly in a kid's book today.

p 113:

..."They may be a-torturin him right now," he went on gloomily, "a-torturin' an' a-teasin' an' a-pryin', an' a-tryin' to make him tell all about us, where our burrows is and all, so's they kin set out poison an' traps an' spring-guns. And how about them sticks tied to his legs Willie was tellin about? Some kind of torture machines likely. Nossir, I don't trust 'em."

After the people are building something in the yard, p 116:

"They're a-buildin' a dungeon," he shouted. "They're a-buildin' a dungeon fer Little Georgie, that's what they're a-doin'. And they'll put him into it behind big iron bars and he'll be a-pinin' there and every time ary one of us touches a dingblasted vegetable they'll torture him and jab him and starve him - and maybe pour boilin' oil onto him!"

p 118:

"It's a gallows," Uncle Analdas pronounced in a sepulchral whisper. "It's a gallows, that's what it is, and they're a-goin' to hang poor Little Georgie onto it."

Three things about this:

1) As a kid it was Uncle A's ideas that I found most freaky (though still not as upsetting as other Tragic Animal Death books).

2) As an adult reading this I now think this is a great book to read to kids if you want to talk about "Hey you know our crazy relative who's sure that [fill in Popular Batshit Conspiracy Theory here] is the complete truth? This character is just like that, and look how wrong he was." Of course Uncle A comes to his senses, and crazy relatives often do not. (I say that, having had some myself.),

3) In 1945 the US was at the end of World War II, which I think has a lot to do with Uncle A's freakout here. From here in the wiki - where you also learn that there was a cook who's been edited out of the story because there were racial stereotypes in her description. So...yeah. I'd have zero fond feelings for this book had that part been left in. (Not that it'd be the first old book I've read with that problem. Sigh.)

Little Georgie is just fine - when the animals gather on the lawn, Mother rabbit says something and Georgie hears her and runs to her. He'd been sitting on the lap of the lady of the house. Who'd nursed him back to health.

What were the people building in the yard? Well, here's where we do get a smack with the ol' Message Mallet, and it's not subtle. (Mallets are rarely known for being subtle.) I'll let the mouse tell it to you - he's speaking to his friend the mole, who has bad eyesight and needs such descriptions, p 122-123:

"Oh, Mole," he said. "Oh, Mole, it's so beautiful. It's him, Mole, it's him - the Good Saint!"

"Him - of Assisi?" asked the Mole.

"Yes, Mole, our Saint. The good St. Francis of Assisi - him that's loved us and protected us Little Animals time out of mind - and, oh, Mole, it's so beautiful! He's all out of stone, Mole, and his face is so kind and so sad. He's got a long robe on, old and poor like, you can see the patches on it.

"And all around his feet are the Little Animals. They're us, Mole, all out of stone. There's you and me and there's all the Birds and there's Little Georgie and Porkey and the Fox - even old Lumpy the Hop Toad. And the Saints hands are held out in front of him sort of kind - like blessing things. And from his hands there's water dropping, Mole, clear, cool water. It drops into a pool there in front of him."

..."It's a fine pool for drinking of, Mole, and at each end of it's shallow like, so the Birds can bathe there. And, oh, Mole, all around the pool is broad, flat stones, a sort of rim, like a shelf or something, and it's all set out with things to eat, like a banquet feast. And there's letters, there's words onto it, Mole, cut in the stones."

"What does it say, Willie, the printing?"

Willie spelled it out slowly, carefully. "It says - There - is - enough - for - all." There's enough for all, Mole. And there is."

All the animals join in eating, while the People sit in their chairs outside, watching. The animals agree that, rather than dividing up the food in the garden (as they've done yearly), they're going to declare it off limits, since the people are leaving out enough food for all of them.

I am known to be a somewhat sappy person, and in this instance I didn't mind the Message Mallet too much - because of the emphasis on the saint belonging to the animals, not the people, and in that recognition the people become part of the community. (Another reason not to mind - it's a relief from the hanging/torturing stuff.) Then again, I'm also the kid who cried when Rankin/Bass's Rudolph shed those crystal tears at not being allowed in reindeer games, so yup, sentimentalist.

A problematic kids' book in ways.

And yet I give it a good amount of stars because Lawson didn't kill off any of his characters to teach me a moral lesson - or just to create A Needless Sad Moment. Because having seen those alternatives, which were meaningless and cruel, I'm thankful for that much. Seems kind of odd now to look at this as a happy alternative.

I don't think I'd give that many stars without considering the artwork though - I still enjoy it. (There's a great illustration of the mice dancing around and teasing the New People's cat, who is sunning himself and doesn't care to chase them. This same cat goes on to wash the recuperating Georgie's ears.)

I never did read Watership Down, or watch the animated film. I was warned away - probably a good thing.

I did love Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH. Now I want to reread that and see how it's changed for me. (I don't remember categorizing the father's death as needless, but I need a refresher.)

4

4

5

5