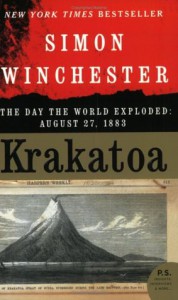

Krakatoa: The Day the World Exploded, August 27, 1883

For much of my reading of this book I've been all "squee" over science and science history. However! I am still the same person who bought and read Death in Yellowstone and Over the Edge: Death in the Grand Canyon (seriously, you would not believe the stupid things people do in these parks), so I can't pretend there's not a "let me marvel at the horror of this trainwreck" sort of thing about volcanoes. But there's no need to feel guilty or ghoulish (too late, I was anyway) - Winchester seems to suspect we might be wondering about what happens to someone caught in an eruption.

First you have to get to chapter 8, and up to that point Winchester teases you along about the greatest explosion ever, etc. But once you're at chapter 8, you get all the eyewitness reports. Then in the section called The Effects, starting on p 239, you get the details. Which could also be titled Ways Die in A Volcanic Eruption. (Note: there's nothing overtly gory in these quotes.) Since not every danger was to occur at Krakatoa, Winchester cites other volcanic events. I've also added some wikipedia links for those who want more science and/or lava photos. (This way I can absorb the educational info while all awe stuck by the horror of these scenarios. Multi-tasking!)

p 241-243: "...Erupted boulders and lumps of partly congealed lava - generally known by the term tephra, from the Greek word for "ash" - scream back down from the skies and flatten anything in their path. Perhaps a relatively small number of people, fewer than a thousand, died in this way from the Krakatoa eruption. All of them were in southern Sumatra, in the path of the prevailing wind: The hot ash that burned them alive had sped westward from Krakatoa on top of a cushion of superheated steam.

Most of the other means with which volcanoes kill their victims were not experienced here. In other eruptions lava flows surround and trap victims and sear them to death. Earthquakes associated with volcanoes destroy buildings, and huge seismically caused cracks in the earth swallow people and buildings in which they live. The terrifyingly fast-moving clouds of hot lava, ash pumice, and incandescent volcanic gases, known... to the rest of the world as pyroclastic flows, sweep people up and incinerate them in seconds...

...Clouds of sulfur-dioxide gas, usually released during eruptions, choke and poison their victims. Clouds of carbon dioxide suffocate them. Clouds of hydrochloric acid gnaw away at their lungs. The torrents of volcanic mud and water slurry that course down the sides of certain volcanoes and that have the Javanese name lahars...carry victims miles away, and drown and bury them.

...There are still more obscure risks: For example, volcanoes that erupt beneath glaciers - which tend not to have too many people living near them - produce sudden floods of melting ice, which have recently been given the exotic Icelandic name jokulhlaups...

However, all of the victims whose deaths can be attributed directly to volcanic activity during the last 250 years, fully a quarter are now believed to have died - drowned or smashed to pieces - as a result of the gigantic waves that were created by the eruptions. The entire Minoan civilization on Crete was supposedly wiped out in 1648 BC when volcanic tephra from the eruption of Santorini - or, much more probably, the tsunamis thrown up by the eruption - destroyed the palaces at Knossos.

...the greatest of these [tsunamis of the last 250 years] by far was the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa. About 35,500 men, women and children died as victims of the two gigantic waves that accompanied or were caused by the death throes of this island-mountain, and they account for more than half of all those in the world who are known ever to have died from waves caused by an erupting volcano.

.................................................................

I found myself really enjoying this book because it suddenly made me remember how much I loved Geology 101. It's hard to go wrong with the excitement that is a volcanic eruption - but before you even get to that point Winchester takes you through all sorts of history. And it's not just the history of the "East Indies" but of the science of volcanoes, which includes the theory of continental drift. I had actually not realized how new that theory is and how recent the belief and the proof for it are.

Am keeping myself from going off on a long tangent here about how fun it is to learn the history of the science as well as the science and how most science classes usually don't include in the history of the scientists working in the field. Because I seriously love that sort of thing.

****************************************************

Contents:

List of Illustrations and Maps

Prelude

One: "An Island with a Pointed Mountain"

Two: The Crocodile in the Canal

Three: Close Encounters in the Wallace Line

Four: The Moments When the Mountain Moved

Five: The Unchaining of the Gates of Hell

Six: A League from the Last of the Sun

Seven: The Curious Case of the Terrified Elephant

Eight: The Paroxysm, the Flood, and the Crack of Doom

Nine: Rebellion of a Ruined People

Ten: The Rising of the Son

Epilogue: The Place the World Exploded

Recommendations for (and, in One Case Against) Further Reading and Viewing

Acknowledgments, Erkenningen, Terima Kasih

Index

Extra additions:

P.S.

About the author - Meet Simon Winchester

About the book - The Haunting Legacy of Krakatoa and Other Natural Disasters: Simon Winchester Responds to the 2004 Tsunami

Read on - A Reading Excerpt from A Crack in the Edge of the World: America and the Great California Earthquake of 1906

Have you read? - More by Simon Winchester

****************************************************

p. 39, building Batavia (now Jakarta): "...A network of narrow streets (Amsterdam-straat, Utrecht-straat) and sixteen canals...was then built in the jungle. The canals in particular, lined with flowering tamarind trees, were also intended to remind the settlers of home; but in fact, since local crocodiles got into the disagreeable habit of sauntering carelessly along them and poking their noses into the residents' doorways, the gesture had for a while rather the opposite effect."

p. 57, Alfred Russel Wallace and Henry Walter Bates: "...The pair, soon inseparable, hunted, collected and cataloged beetles in every corner of Leicestershire and points beyond - with Bates publishing his first paper "On Coleopterous Insects Frequenting Damp Places," the title telling us perhaps more about Leicestershire than about beetles."

Alfred Russel Wallace seems to be much loved by the author - and after reading this section I wanted to read more. A few more quotes to give you an idea of the man (I felt badly for him at the "losing all his research" part):

p 57-8: ...the square-rigger Helen, in which he was bringing home his valuable collections of Amazon specimens, caught fire and sank in mid-Atlantic, and Wallace spent ten days in a longboat before being picked up near Bermuda, He wrote two books on his experiences. Darwin, who trawled through both looking for evidence to bolster his own fast-coalescing ideas on biological variation, natural selection, and species origin, found them frustrating. "Not enough facts," he harrumphed, cruelly unaware that Wallace had lost not only his notes but his specimens, all gone down with the foundered ship.

...Wallace's sudden understanding of evolution is one of the most romantic tales of modern science, ranking with the sudden achievements of Archimedes and Galileo, Becquerel and Newton, Fleming and Marie Curie. The vision came to him not in a bathtub or in Pisa, or on a Paddington windowsill, or under an English apple tree - but in a grass hut on stilts, in a village on the island of Ternate, during a bout of jungle fever. There are not a few who believe that it is the Spice Islands, and not the Galapagos, that one day should come to be recognized as the true birthplace of the science of evolution.

p 61: ...Darwinism is the accepted word, invented by Wallace and the title of one of his later books. Wallace never displayed in public a scintilla of bitterness, and contentedly and generously gave Darwin all the credit. His classic, The Malay Archipelago (in which Wallace tried to popularize the idea of a zoogeographical division, which so neatly coincides with the phenomenon that gives birth to Krakatoa), is dedicated to Darwin, "to express my deep admiration for his genius and his work." He remained loyal, almost servile - the ever revolving little moon around Darwin's glittering and far grander planet.

Multiple wikipedia links in there in case you too didn't get enough science history in school (some of those I've learned via pop culture and books rather than in any science class, which seems odd). Winchester refers to multiple books by Wallace, and happily many of them are online. In particular The Wonderful Century (Internet Archive link). More texts here at Gutenberg. Just from glancing through some of them, I think that Wallace's writing seems much more readable than many of his contemporary scientists.

Speaking of pop culture - to this day I can't see the word archipelago without thinking of The Archipelago of Last Years. Because that's what gleefully absorbing a lot of stop motion animation when you are young will do to your brain. (I regret nothing!!!!) Great word, archipelago. (Even though I never feel like I'm spelling it correctly.)

There are a lot of stories in this book that you could see easily turning into a book on their own. At this point I'm amazed the book is a mere 416 pages.

p 126, discussing the Book of Kings by Ranggawarsita, and when he mentions writing on leaves those are indeed palm leaves: "...So here we have it: an account that arrives from an ancient god via an enigmatic tenth-century king who dictated material to scribes who wrote on leaves, and then through the good offices of a nineteenth-century court poet who, yes, could read those leaves but who was clearly also a man much taken to flights of fancy. Small wonder that the scientific community has received this basic story of Krakatoa's first recorded eruption with a healthy degree of skepticism."

p 133: "...The Dutch who settled in the seventeenth-century Batavia were not an especially content people, by all accounts. Their lives were a succession of uncomfortable trials. They were seldom fully well: They tended to succumb to a variety of tropical ills - malaria, cholera, dengue fever - and they were morbidly afraid of the air on which they suspected the responsible germs were borne. The foul smells from the coast, brought in by the sea breezes that usually began to blow at breakfast time, prompted everyone in the city to keep their doors and windows firmly shut until dusk; and then to shut them once more soon after, to keep out the evening mosquitoes. Everyone bathed in the city canals. "The ladies unblushingly dived into these general public bathtubs," wrote Bernard Vlekke, "a custom which was vainly forbidden...because the canals were used as sewers and were therefore, rather filthy." "

Remember the television show with James Burke called Connections? A lot of the story of Krakatoa reminds me of this - in a good way. There are so many inter-connected stories going on here - social and cultural, new technology, science, art, etc.

p 194: "...It was thanks to the combined agencies of all those involved - to Samuel Morse, to the directors of the India Rubber, Guetta Percha & Telegraph Works Company, to the Eastern Telegraph Company, to the Committee of Lloyd's, to Reuter, and to the small network of eager correspondents in Anjer, Batavia, and London - that this first remarkable story started to be told."

Why hasn't anyone written a biography of Paul Julius Freiherr von Reuter (Baron de Reuter) and the creation of the Reuters news agency yet? He's mentioned in a lot of media history books, but no one book of just his story. That I can find. Yet. (I suspect there may be one in German somewhere, maybe?)

11

11